The surprising benefits of exercising with friends

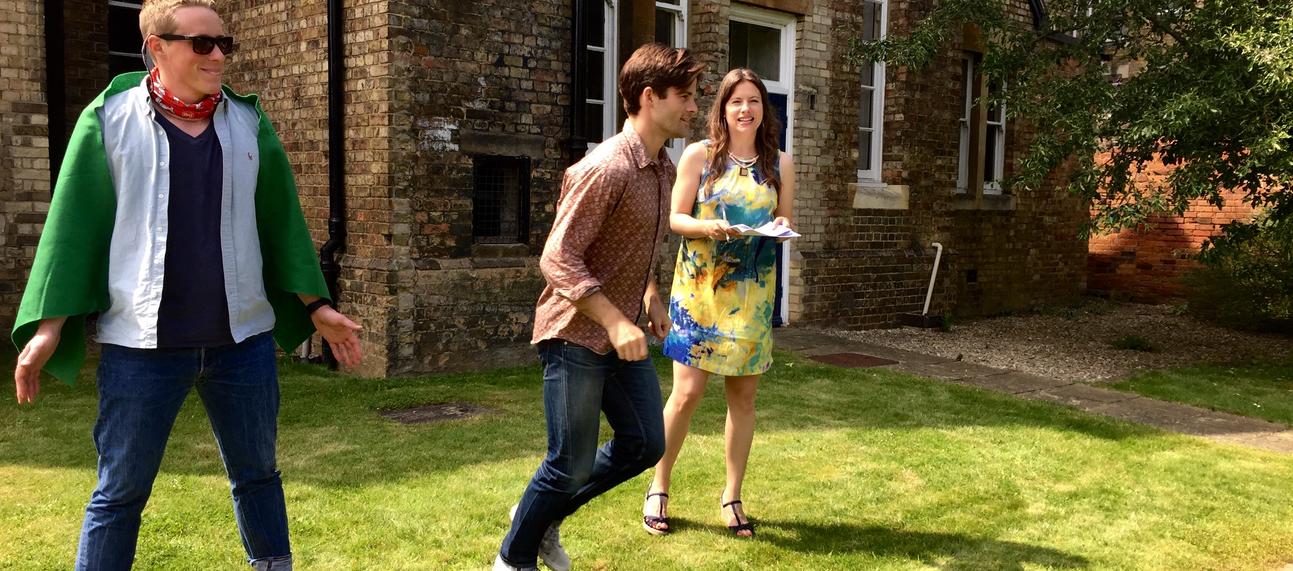

Dr Arran Davis explores the physical and social benefits of exercising with others in this new BBC Ideas film

Did you know that exercising with friends comes with its own unexpected benefits?

Dr Arran Davis, Postdoctoral Researcher within the Social Body Lab (Centre for the Study of Social Cohesion) tells us more in this video, made in partnership with BBC Ideas and Oxford University's Social Sciences Division.

The surprising benefits of exercising with friends

The research behind the video

Dr Arran Davis answers some key questions and delves deeper into his research carried out in collaboration with Professor Emma Cohen.

Why does exercising with friends benefit our workouts?

Our evolutionary perspective views humans as a highly social species – we rely on other people for the material and cultural resources we need to both survive and thrive. And this would have been especially true for our ancestors. So, we expect that humans evolved to (tacitly) associate supportive social environments with relative resource abundance.

And this has important consequences for how our bodies manage their resources. During exercise, fatigue functions to keeps us safe by making us stop before we get hurt or become dangerously exhausted. Interestingly, research suggests that fatigue is ultimately determined not by our muscles but by how we feel; our mind forces us to stop even when our muscles have something left to give. But this cautious system becomes a bit less careful when our social environments signal to us that we are safe and have the care and resources needed to recover. So, when we are with our friends, we start feeling fatigued a bit later, and this can both improve our workouts and make them more enjoyable.

Fatigue is ultimately determined not by our muscles but by how we feel; our mind forces us to stop even when our muscles have something left to give. But this cautious system becomes a bit less careful when our social environments signal to us that we are safe.

How can moving together make us feel closer and more connected?

There are probably two related but distinct routes through which this happens. At the neurobiological level, we release endorphins and endocannabinoids during exercise; these chemical messengers make us feel happy and content, and they are responsible for the ‘runner’s high’. Research has shown that sharing these feelings with others can help us feel closer and more connected. But on top of this, moving together, say in a team sport or dance, also involves collaboration, coordination, and cooperation. Doing these collaborative activities can lead us to trust each other more and to view each other as cooperative partners. In short, they help us build friendships. I’d argue that group exercise is special because it provides us with both neurobiological and cognitive paths to social bonding.

Are social relationships really that important for our health?

They really are! Many longitudinal studies have tried to understand the lifestyle factors underpinning long-term health. These studies follow large samples of people for years or even decades. Researchers ask participants about their daily habits - questions about their diet, how much they smoke, exercise, and see their friends, about their occupation and income, etc. They then also monitor how often participants get sick and record when they die.

These studies consistently show that being socially connected is one of the strongest predictors of good mental and physical health. One meta-analysis (a technique for summarizing the results of a bunch of other studies) even found that lacking positive social connections is as dangerous for our health as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day! This BBC Radio 4 More or Less episode has a great summary of how this research was conducted.

Why do social relationships affect our health?

In humans, like other social animals, isolation signals relative danger and resource scarcity. So, we respond to social isolation in a way that protects us from these risks; we get more stressed and activate the fight or flight response, we become more sensitive to pain and fatigue, and we can even feel depressed. These short-term responses may have helped our ancestors survive social isolation by allowing them to better deal with physical threats and resource scarcity. But when chronically activated in our modern world (think about chronic stress), they slowly degrade the physiological systems needed for long-term health, causing us to get sick more often and to die sooner.

What kind of research do you do to understand how social environments affect our workouts?

We do a mixture of experimental and observational research. Our experiments test the hypothesis that social support reduces fatigue and enhances performance during exercise. These experiments are a bit tricky to conduct; we can’t just have people exercise with friends in one condition and on their own in another, because that would lead to confounds. For example, people might just try harder in the social condition to ‘show off’ to their friends. So, we manipulate the social environment surrounding participants, but they exercise alone in all experimental conditions to avoid these social confounds. We’ve had participants come to experimental sessions either alone or with a friend (who warms up with them and then waits for them in another room), or we simply show participants either the photo of someone they feel supported by or the photo of a stranger. Our results show that even just viewing the photo of a supportive friend can make exercise feel less tiring and allow us to produce greater outputs.

An example of our observational research is our study on parkrun, a free, weekly, community-based 5 km run for all ages and skill levels that happens at over 2,000 locations worldwide. We followed over 100 parkrunners for an 18-week period; each week, participants answered questions about how they felt during their runs, and about their social interactions with other parkrunners. We found that parkrunners who attended with family and friends and who felt supported by the parkrun community enjoyed their runs more and felt more energised, and that these feelings of increased energy led them to run faster 5 km times. Through a mix of experimental and observational research, we can better understand the causal mechanisms underpinning real-world behaviours and outcomes.

Where did the ideas for this research come from?

These ideas are not new; many of us have friends from sports teams or exercise and dance classes, and the links between team cohesion, perceptions of support, and sporting success have long been assumed by amateur and professional athletes alike. But we’ve also looked at these phenomena in the sports teams we’ve been a part of. Much of this research was done by myself and Jacob Taylor when we were DPhil (PhD) students in Oxford. Jacob and I were both student athletes; I was a javelin thrower on the Oxford University Blues Athletics team, and Jacob was captain of the Oxford University Blues Rugby Team. We used our experiences training with these teams to inform the questions we asked and to shape the studies we designed.